In 2003, I succeeded to the legacy of Malcolm X inherited at the Organization of African Unity (OAU) by being the lone African American at the African Union (AU) when they amended its constitution to include the African Diaspora. You can read my story here. I received the same instructions that Malcolm X received, and started the same work that he started. Below are excerpts from the Jubilee Commemoration Exhibition of His Imperial Majesty Emperor Haile Selassie I First Visit to the United States (1954) presentation I gave at the Marcus Garvey Center in Brooklyn, New York, May 29, 2004 and taken from my book, 50th Anniversary of His Imperial Majesty Haile Selassie I First Visit to the United States (1954-2004)

THE HIGH-POINT OF US-AFRICAN RELATIONS: BROWN VS. BOARD OF EDUCATION DECISION AND THE VISIT OF HIS IMPERIAL MAJESTY, EMPEROR HAILE SELASSIE I OF ETHIOPIA.

It has already been stated that His Imperial Majesty’s Visit to the United States in 1954 marked the high-point of US-Africa relations. This was represented by the US-Ethiopia Mutual Defense Agreement and the establishment of the Kagnew communications facility which became the major US sigint ("signal intelligence") listening station monitoring all High Frequency radio messages. It was also represented in the linking of the civil rights struggle of Africans in American with the struggle for African Liberation on the African Continent. Sundiata Acoli, an Afrikan Liberation soldier imprisoned in America, writes:

“Afrikans from Afrika, having fought to save European independence, returned to the Afrikan continent and began fighting for the independence of their own colonized nations. Rather than fight losing Afrikan colonial wars, most European nations opted to grant ‘phased’ independence to their African colonies. The US now faced the prospect of thousands of Afrikan diplomatic personnel, their staff, and families coming to the UN and wandering into a minefield of incidents, particularly on state visits to the rigidly segregated [Washington] DC capital. That alone could push each newly emerging independent Afrikan nation into the socialist column. To counteract this possibility, the US decided to desegregate. As a result, on May 17, 1954, the US Supreme Court declared school segregation illegal.”

Just prior to His Imperial Majesty’s arrival in the United States, an editorial in the Ethiopian Herald newspaper of May 22, 1954 stated, “So intermeshed are the interests of our present day world that whatever happens in one part may have repercussions in wide areas elsewhere. The United States Supreme Court’s decision last Monday on segregated state schools in that country takes its place in this category of events.” Sensitive to embarrassment before the world that the spectre of racial segregation, particularly in education, might have during the visit of a Black Emperor of Ethiopia, the US passed the Brown vs. Board of Education decision when it did, just one week before His Imperial Majesty’s arrival, in order to “show off” the progress the US was making in race relations. According to the United States Government's Amicus Curiae brief to the US Supreme Court,

“It is in the context of the present world struggle between freedom and tyranny that the problem of racial discrimination must be viewed . . . For discrimination against minority groups in the US has an adverse effect upon our relations with other countries. Racial discrimination furnishes grist for the Communist propaganda mills, and it raises doubts even among friendly nations as to the integrity of our devotion to the democratic faith.”

The Chicago Defender newspaper ran an article during His Imperial Majesty’s visit entitled “Integration On Display For Selassie At Capital” and stated that,

“Colored Washingtonians were much in evidence both in official and non official capacities here Wednesday as the nation’s capital greeted Emperor Haile Selassie, the Emperor of Ethiopia. . . . The government lost no opportunity to present colored Americans in a favorable light during the Emperor’s stay here. It was obvious that the state department realized that his visit on the heels of the Supreme Court decision offered a good opportunity to counter Communist racial propaganda which has plagued this nation in world forums.”

A Cleveland Call and Post editorial stated that, “The nation’s Chief Executive [President Eisenhower] has repeatedly stated that the stigma of racial discrimination is the greatest weakness in our defense against world communism . . . .” Addressing the issue after receiving an Honorary Doctorate of Laws from Howard University on May 28, Emperor Haile Selassie said, “the World is becoming increasingly aware of the importance of contributions made by colored peoples everywhere to higher and broader standards of social concepts. Events of the recent days, here in the United States, have brilliantly confirmed before the world the contributions which you have made to the principle that all men are brothers and equal in the sight of God.”

Asked by a reporter at a New York Press Conference on June 1, 1954 what he thought about the recent United States Supreme Court decision outlawing racial segregation in the public schools, His Imperial Majesty Haile Selassie replied,

“This historic court decision resting on your Constitution will win the esteem of the entire world for the United States. And in particular, it will win the esteem of all the colored people of the world.”

Asked the same question in San Francisco on June 14, His Imperial Majesty said, “The decision will not only strengthen the ties between Ethiopia and the United States, but will also win friends everywhere in the world.”

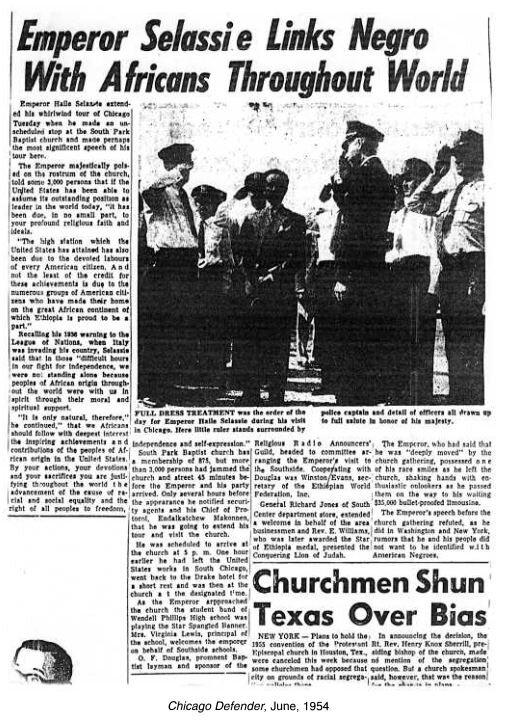

Another article, which appeared on June 8, 1954, was headlined, “Emperor Selassie Links Negro With Africans Throughout World.” According to the Chicago Defender, Haile Selassie’s Special Message to the African in America:

“My message to the colored people of the United States is that they continue to press forward with determination their social and intellectual advancement, meeting all obstacles with Christian courage and tolerance, confident in the certainty of the eventual triumph of justice and equality throughout the world. The people of Ethiopia feel the strongest bond of sympathy and understanding with the colored people of the United States. We greatly admire your achievements and your contributions to American life and the tremendous development of this great nation.”

Just before the start of Haile Selassie’s visit to the US, the British in East Africa launched “Operation Anvil” against the mounting strength of the African Freedom Fighters called “Mau Mau”. More than 40,000 British troops captured 26,500 “suspects” and held them in concentration camps.

General Musa Mwariama and Kenyan President Jomo Kenyatta

Just over a year later, on December 1, 1955, Rosa Parks embodied that courage and determination and defied Montgomery, Alabama’s bus segregation laws by refusing to give her seat to the white man, kicking off the civil rights movement in America. By 1957, Ghana had become the first African nation to achieve its independence.

By January 4, 1965, the New York Times was reporting that Malcolm X had gotten 33 African Heads of State to support his Organization of Afro American Unity (OAAU) petition to the United Nations and that the US State Department, the CIA and the FBI noticed that African leaders were now openly attacking the US.

Malcolm X and Ghana President Kwame Nkrumah

By February 16, 1965, Malcolm X was denouncing the 1954 Brown vs. Board of Education decision as “Tokenism”:

“From 1954 to 1964 can easily be looked upon as the era of the emerging African state. And as the African state emerged . . . what effect did it have on the Black American? When he saw the Black man on the [African] continent taking a stand, it made him become filled with the desire to take a stand . . . Just as [the US] had to change their approach with the people on the African continent, they also began to change their approach with our people on this continent. As they used tokenism . . . on the African continent . . . they began to do the same thing with us here in the States . . . . Tokenism . . . every move they made was a token move . . . . They came up with a Supreme Court decision that they haven’t put into practice yet. Not even in Rochester, much less in Mississippi.”

Relentlessly seeking to educate the African in America about Africa, Malcolm X began making Africa’s independence struggle and its relationship to the civil rights struggle a focus of his speeches.

Malcolm X was killed on February 21, 1965. Two weeks later, the New York Times ran a story headlined

“World Court Opens Africa Case Monday” which stated that “The International Court of Justice will open oral proceedings Monday in a case linking the segregation struggle of the American Negro and the fate of 430,000 African Bantus and bushmen . . . .

At issue is a four-year effort by Ethiopia and Liberia to bar South Africa from applying her race separation or apartheid doctrine in South West Africa which she controls. The two African complainants, searching for arguments to defeat race-separation policy, have hit on the obvious parallels between the two separations. Almost certainly they will cite the American school segregation cases beginning with the history making decision of May, 1954 in Brown vs. Board of Education, in which the Supreme Court found that separate educational facilities are inherently unequal.”

Just before Malcolm X’s murder, Burundi Prime Minister, Pierre Ngendandumwe, a major supporter of the OAAU petition, was assassinated by Gonzlave Muyinzi, a man who worked at the US Embassy where the CIA was located. Four days after Malcolm X’s murder, a Kenyan government official who supported the OAAU petition was assassinated.

Regarding the South West Africa case at the International Court of Justice, at issue was the policy of racial segregation. The San, Khoihoi, Ovambo and Herero tribes lived in general isolation from Europeans until Portuguese explorer Batolomeau Dias landed in 1488. He was followed by hunters, missionaries, explorers and a small number of British and American whalers. The Dutch took over the only deep water port in Namibia (Walvis Bay) but this was taken over by the British in the 18th century. A German merchant called “Ledertitz” set up a town on the coast and it was from this foothold that German South West Africa was established in 1884. In the next three decades, the Germans bought or stole all the land of the natives, and bloodily suppressed African resistance. The biggest uprising against the Germans was made by the Herero, whose revolt in 1904 cost 60,000 lives becoming the first genocide of the Twentieth Century. In 1915, during World War I, the German Colony was conquered by military forces of South Africa. Germany renounced sovereignty over the region in the Treaty of Versailles, and in 1920 the League of Nations granted South Africa a mandate over the territory. The “mandate” stated that the well being and development of those peoples in former enemy colonies not yet able to stand by themselves formed a “sacred trust of civilization” and that “the tutelage of such peoples should be entrusted to advanced nations . . . who are willing to accept it.” This meant that the racist white minority of South Africa had, under the Covenant of the League of Nations, accepted the responsibility to do the utmost to promote the material and moral well-being and the social progress of the inhabitants of the country.

In 1946 the United Nations General Assembly requested South Africa to submit a trusteeship agreement to the UN to replace the mandate of the defunct League of Nations; South Africa refused to do so. In 1949, a South African constitutional amendment extended parliamentary representation (and thereby the racist policy of apartheid) to South West Africa. The International Court of Justice, however, ruled in 1950 that the status of the mandate could be changed only with the consent of the UN. South Africa subsequently refused to accede to UN demands concerning a trusteeship arrangement. Aroused by the steps that the government of South Africa was taking to establish apartheid in the mandated territory, Ethiopia and Liberia took the case to the International Court of Justice. It was their contention that, since the Brown vs. Board of Education decision ruled that racial segregation was unfair, did not promote the material and moral well-being and social progress of blacks, and violated their human rights, then applying racial segregation in the form of apartheid in South West Africa could not be said to promote the moral and material well-being and social progress to the black people in that territory, and thus, South West Africa should be granted their independence.

On December 7, 1960, HIM Haile Selassie remarked, in response to a toast by Liberian President William Tubman, that

“This same spirit of collaboration on problems of mutual concern continuing at an accelerated pace today in the policies which these two African states are pursuing to the end of eradicating racial discrimination, that ignoble and most infamous of prejudices, from the face of the earth. Ethiopia and Liberia are today pressing a legal action before the International Court of Justice at the Hague, for the lifting of the mandate held by the Republic of South Africa over the territory of South-West Africa. We re-affirm here now our determination to pursue this course to its successful conclusion.”

On February 2, 1962, HIM Haile Selassie said,

“The apartheid policy of the racist government of the white minority in South Africa continues to subject our African brothers, who constitute the overwhelming majority in that country, to untold humiliation and oppression . . . .the unfortunate condition in which our African brothers find themselves in South-West Africa under the notorious and deplorable policy of apartheid and ruthless administration of South Africa is equally depressing and intolerable. However, We are convinced that before long the continued efforts of the United Nations and the legal proceedings instituted at the International Court of Justice by our Government and that of our sister state Liberia will bear fruit.”

Then, on May 26, 1965, just two months after the murder of Malcolm X and the New York Times article announcing the start of the South West Africa case and linking it with Malcolm X’s petition to the United Nations, HIM Haile Selassie said,

“In South Africa and South West Africa, the policies of apartheid and oppression are becoming increasingly unbearable. The South African Government [note: like the US Government Federal Bureau of Investigations Counter-Intelligence Program or COINTELPRO] is accelerating its ruthless campaign: a methodological campaign of arresting daily, detaining without trial and torturing the Africans and their leaders who are struggling for their fundamental human rights and freedom. All the peace-loving countries of the world must act together to force the colonial governments of South Africa and Portugal to desist from these policies - policies which are inhuman, policies which are detrimental to the peace and security of the ENTIRE WORLD - and grant independence and freedom to these oppressed people.”

A year later, while at the Organization of African Unity on July 7, 1966, HIM Haile Selassie said,

“You are meeting today in this very Hall which gave birth to the Organization of African Unity barely two and a half years ago in order to consider and find a solution to the Southern Rhodesian situation which has posed a grave challenge not only to the OAU but also to the independence of Our individual states and indeed to the national liberation movements of Angola, Mozambique, South West Africa, South Africa, . . . All forces of good, wherever they may be found, must be mobilized to uproot the white supremacists in Rhodesia and in Southern Africa. All freedom loving peoples must co-operate to destroy this deadly cancer of human liberty and equality. After all, at issue is not the loss of freedom to four million Africans but the survival of human liberty. The world, therefore should not condone the perpetration of one of the greatest political crimes in human history.”

On July 18, 1966, the International Court of Justice rendered its Judgment in Ethiopia v. South Africa; Liberia v. South Africa:

“In its Judgment on the second phase of the cases the Court, by the President’s casting vote, the votes being equally divided (seven-seven), found that the Applicant States could not be considered to have established any legal right or interest in the subject matter of their claims and accordingly decided to reject them.”

Four months later, at the opening session of the OAU on November 6, 1966, His Imperial Majesty Haile Selassie stated:

“For a number of years now the problem of South West Africa has become the major concern of the African countries. Liberia and Ethiopia, as former members of the League of Nations, acting on behalf of all African States, had sued South Africa for violating her mandate in South-West Africa by introducing the policy of apartheid into that territory and by failing in her obligation to promote the interest of the African population. After six years of litigation, the International Court of Justice decided that the two states did not establish legal status in the case to stand before the Court, thus reversing its judgment of jurisdiction given in 1962. This unfortunate decision has profoundly shaken the high hopes that mankind had placed in the International Court of Justice. The faith man had that justice can be rendered is shattered and the cause of Africa betrayed.”

Apartheid laws of South Africa, by this time, had been extended to the country. The UN continued to debate the question, and in June 1971 the International Court of Justice ruled that the South African presence in South West Africa was illegal. However, South Africa continued to govern the territory. As a result, the South West African People’s Organization (SWAPO), a black African nationalist movement led by Sam Nujoma, escalated its guerrilla campaign to oust South Africans. South Africa continued to resist eviction until December 1988, when it agreed to allow “Namibia” to become independent.

Thus, one can see that the victory of Haile Selassie over Mussolini and the Fascists in 1941, and HIM Haile Selassie's "Coming to America" actually provoked the Brown vs. Board of Education decision. The case was significant not only in terms of American history, but in terms of the African Liberation struggle and, therefore, world history. Today, even African American scholars do an injustice by failing to link the Brown v Board of Education decision to the African Liberation struggle led by His Imperial Majesty Emperor Haile Selassie I. As a result, the public is taught that the Brown vs. Board of Education was only a significant element in the civil rights struggle instead of the human rights struggle which Malcolm X was illustrating back in 1964-65.

AFTER BROWN VS BOARD OF EDUCATION: Malcolm X, Martin Luther King and Repatriation

In 1954, Ethiopian Emperor Haile Selassie I came to America just days after the Brown vs. Board of Education decision heralded the end of the Jim Crow era. For 18 months before and for six weeks during HIM’s visit to the United States, HIM Haile Selassie began a Repatriation recruitment program for Black people in New York, Pennsylvania, Washington, Virginia, North Carolina, Florida, Georgia, Alabama, Tennessee, Kentucky, Ohio, and Illinois. HIM Haile Selassie I had granted land in Shashemane Ethiopia, had made a constitutional provision for the Repatriates immediate citizenship, and promised free transportation, a house rent-free, competitive salaries, and paid three-months vacations with round-trip tickets to America and back to Ethiopia. Black Americans interested in the Repatriation offer were instructed to fill out an application (Repatriation Census) available from the Ethiopian Embassy. As a result, Black America was faced with the choosing between Integration and Repatriation.

Black America chose integration.

During this time from 1954 to 1961, Malcolm X and Martin Luther King began their growth as emerging leaders – Malcolm X for Black Muslims, and Martin Luther King for Black Christians. The Black Muslims began to advocate for a separate black “nation within a nation” in the United States “Black Belt” southern territory. Martin Luther King Jr, whose father was in charge of the Georgia National Baptist Convention Ethiopia Day fundraising for Emperor Haile Selassie I in the 1930’s, advocated for a “civil rights” platform of integration into the United States based on principles of equality and justice.

In the early 1960’s, Ras Mortimo Planno, a major figure in the Rastafari Repatriation Movement, was in New York and he and Malcolm X began to discuss the solution to the condition of the Black man in America. Having toured Africa and spoken with African Heads of State including HIM Haile Selassie I, General Nnamdi Azikiwi of Nigeria, President Kwame Nkrumah of Ghana, President William Tubman of Liberia and Prime Minister Milton Margai of Sierra-Leone, Ras Mortimo Planno suggested to Malcolm X that if the Black Muslim plan for a separate, Black Nation in the within the United States failed, that the only solution would be Repatriation. Since the late sixties, both the Republic of New Afrika and the Nation of Islam have failed to establish a government for the Black “nation within a nation”. Thus, the past fifty years have been the result of the choice of integration.

Both Ras Mortimo Planno and Malcolm X, upon returning to the West after visiting with African Heads of State, began collecting the names of those who wanted to Repatriate. Ras Junior Negus (secretary of the 2003 Rastafari Global Reasoning in Jamaica) wrote to IRIE on April 1, 2004: “I am quite aware of the census. This was the work HIM had given Planna from 61. He started from Kingston to Porus and has been no further. . . . Planna, after returning from the 2nd mission was told by His Majesty and different governments they visited to collect the names of the ones who want to return to Africa.”

Likewise, Malcolm X stated,

“One of the things I saw the OAAU doing from the very start was collecting the names of all the people of African descent who have professional skills, no matter where they are. Then we could have a central register that we could share with independent countries in Africa and elsewhere. Do you know, I started collecting names, and then I gave the list to someone who I thought was a trusted friend, but both this so-called friend and the list disappeared. So, I’ve got to start all over again.” (Jan Carew, Ghosts In Our Blood, p. 61)

“The 22,000,000 so-called Negroes should be separated completely from America and should be permitted to go back home to our African homeland which is a long-range program; so the short-range program is that we must eat while we’re still here, we must have a place to sleep, we have clothes to wear, we must have better jobs, we must have better education; so that although our long-range political philosophy is to migrate back to our African homeland, our short-range program must involve that which is necessary to enable us to live a better life while we are still here.” (Interview with Malcolm X, by A.B. Spellman, Monthly Review, Vol. 16, no.1 May 1964)

On June 28, 1964, six weeks after Malcolm’s return to New York from Africa, he announced the formation of the Organization of Afro-American Unity (OAARU). “It was formed in my living room,” remembers John Henrik Clarke.

“I was the one who got the constitution from the Organization of African Unity in order to model our constitution after it. Malcolm’s joy was that we could match up [our constitution with the African one]; we could find parallels between the African situation and the African-American situation – that plus a whole lot of other things we agreed with that had nothing to do with religion, because we agreed with the basic struggle. We agreed on self-reliance, about what people would have to do, and that an ethnic community was really a small nation and that you need everything within that community that goes into a small nation, including a person who would take care of the labor, the defense, employment, morality, spirituality . . . . “ (David Gallen, As They Knew Him, p.79-80).

Thus, Malcolm X, along with John Henrik Clarke, wrote the following into the Organization of Afro- American Unity (OAAU) Basic Unity Program

i. Restoration: “In order to free ourselves from the oppression of our enslavers then, it is absolutely necessary for the Afro-American to restore communication with Africa . . .

ii. Reorientation: “ . . . We can learn much about Africa by reading informative books . . . “

iii. Education: “ . . . The Organization of Afro-American Unity will devise original educational methods and procedures which will liberate the minds of our children . . . We will . . . encourage qualified Afro-Americans to write and publish the textbooks needed to liberate our minds . . . . educating them [our children] at home.”

iv. Economic Security: “ . . . After the Emancipation Proclamation . . . it was realized that the Afro-American constituted the largest homogeneous ethnic group with a common origin and common group experience in the United States and, if allowed to exercise economic or political freedom, would in a short period of time own this country. WE MUST ESTABLISH A TECHNICIAN BANK. WE MUST DO THIS SO THAT THE NEWLY INDEPENDENT NATIONS OF AFRICA CAN TURN TO US WHO ARE THEIR BROTHERS FOR THE TECHNICIANS THEY WILL NEED NOW AND IN THE FUTURE.

On December 12, 1964, Malcolm answered a question about going back to Africa at the Haryou-Act Forum for Domestic Peace Corps in Harlem. Said Malcolm,

“You never will have a foundation in America. You’re out of your mind if you think that this government is ever going to back you and me up in the same way that it backed others up. They’ll never do it. It’s not in them. . . . . By the same token, when the African continent in its independence is able to create the unity that’s necessary to increase its strength and its position on this earth, so that Africa too becomes respected as other huge continents are respected, then, wherever people of African origin, African heritage or African blood go, they will be respected – but only when and because they have something much larger that looks like them behind them. With that behind you, you can do almost anything under the sun in this society . . . And this is what I mean by a migration or going back to Africa – going back in the sense that we reach out to them and they reach out to us. Our mutual understanding and our mutual effort toward a mutual objective will bring mutual benefit to the African as well as to the Afro-American. But you will never get it by relying on Uncle Sam alone. You are looking in the wrong direction. Because the wrong people are in Washington D.C. and I mean the White House right on down . . . . “ (Malcolm X Speaks, p.210-2)

William Kunstler, who served as special trial counselor to Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., in the early 1960’s, speaks of a telephone conversation between Malcolm and Dr. King on February 14, 1965:

“There was sort of an agreement that they would meet in the future and work out a common strategy, not merge their two organization – Malcolm had the Organization Afro-American Unity and Martin, of course, was the president of the Southern Christian Leadership Conference – but that they would work out a method to work together in some way. And I think that that quite possibly led to the bombing of Malcolm’s house that evening in East Elmhurst and his assassination one week later.” (David Gallen, As They Knew Him, p. 84)

Among the most promising area of mutual collaboration among Malcolm X and Dr. King was the area of Repatriation. For as early as April of 1957, Dr. King had already begun to promote going back to Africa. In his sermon ”The Birth of a New Nation” delivered at Dexter Avenue Baptist Church on April 7, Dr King stated,

“Yes, there is a wilderness ahead, though it is my hope that even people from America will go to Africa as immigrants, right there to the Gold Coast, and lend their technical assistance, for there is great need and there are rich opportunities there. Right now is the time that America Negroes can lend their technical assistance to a growing new nation. I was very happy to see already people who have moved in and making good. The son of the late president of Bennett College, Dr. Jones, is there, who started an insurance company and is making good, going to the top. A doctor from Brooklyn, New York, had just come in that week and his wife is also a dentist, and they are living there now, going in there and working, and the people love them. There will be hundreds and thousands of people, I’m sure, going over to make for the growth of this new nation. And Nkrumah made it very clear to me that he would welcome any persons coming there as immigrants and to live there. . . . There is a great day ahead. The future is on its side. Its going now through the wilderness, but the Promised Land is ahead.

To Dr. King, that Promised Land was Ghana:

“Now don’t think that because they have 5 million people the nation can’t grow, that that’s a small nation to be overlooked. Never forget the fact that when America was born in 1776, when it received its independence from the British Empire, there were fewer, less than four million people in America, and today its more than a hundred and sixty million. So never underestimate a people because it is small now. America was smaller than Ghana when it was born . . . Ghana has something to say to us. It says to us first that the oppressor never voluntarily gives freedom to the oppressed. You have to work for it. And if Nkrumah and the people of the Gold Coast had not stood up persistently, revolting against the system, it would still be a colony of the British Empire. Freedom is never given to anybody, for the oppressor has you in domination because he plans to keep you there, and he never voluntarily gives it up. And that is where the strong resistance comes. Privileged classes never give up their privileges without strong resistance. . . . If we wait for it to work itself out, it will never be worked out. Freedom only comes through persistent revolt, through persistent agitation, through persistently rising up against the system of evil. The bus protest is just the beginning. . . . Ghana reminds us that whenever you break out of Egypt, you better get ready for stiff backs. You better get ready for homes to be bombed. You better get ready for a lot of nasty things to be said about you, because you’re getting out of Egypt, and whenever you break loose from Egypt, the initial response of the Egyptian is bitterness. It never comes with ease. It comes only through hardness and persistence of life. Ghana reminds us of that. . . . But finally, Ghana tells us that the forces of the universe are on the side of justice. That’s what it tells us now. You can interpret Ghana any kind of way you want to, but Ghana tells me that the forces of the universe are on the side of justice. That night when I saw that old flag coming down and the new flag coming up, I saw something else. That wasn’t just an Ephemeral, evanescent event appearing on the stage of history, but it was an event with eternal meaning, for it symbolizes something. That things symbolized to me that an old order is passing away and a new order is coming into being. An old order of colonialism, of segregation, of discrimination is passing away now, and a new order of justice and freedom and goodwill is being born. That’s what it said: that somehow the forces of justice stand on the side of the universe, and that you can’t ultimately trample over Gods children and profit by it.”

Just after the bombing of Malcolm X’s house on February 14, 1965, Malcolm gave a speech at the Ford Auditorium. He said,

“So when you count the number of dark-skinned people in the Western Hemisphere you can see that there are probably over 100 million. When you consider Brazil has two-thirds what we call colored, or nonwhite, and Venezuela, Honduras and other Central American countries, Cuba and Jamaica, and the United States and even Canada – when you total all these people up, you have probably over 100 million. And this 100 million on the inside of the power structure is what is causing a great deal of concern for the power structure itself. So we saw that the first thing to do was to unite our people, not only unite us internally, but we have to be united with our brothers and sisters abroad. It was for that purpose that I spent five months in the Middle East and Africa during the summer.’

Malcolm X was assassinated before he was able to collect the names and the OAAU was successfully destroyed by the FBI. However, the Repatriation program survived. According to William Sales Jr.,

“An aspect of SNCC’s international orientation which survived the organization was the establishment of the Pan-African Skills Project. This was an idea of Forman’s, which reflected Malcolm’s desire to provide African American technical assistance personnel to developing African nations, which came to life in 1969. Foreman’s leadership in the Detroit Black Economic Development Conference of 1969 resulted in the development of a practical program for that old nationalist staple, reparations to African Americans. The Black Manifesto presented at New York’s Riverside Church on May 4, 1969 resulted in increased funding for programs controlled by Blacks. One of the most effective of these was the Pan-African Skills Project. Headed up by former SNCC chairperson, Irving Davis, the Project sent over 250 Afro-American teachers, technicians, and professionals to Tanzania and a smaller number to Zambia. It was probably one of the two most concrete manifestations of Pan-Africanism to emerge subsequent to Malcolm’s initiatives of 1964.” (Malcolm X and the Organization of Afro-American Unity p. 1999).

Fanon C. Wilkins of Syracuse University writes,

“Founded in January 1970 by Irving Davis, former Deputy Chairman of the International Affairs Commission of the Student Non-Violent Coordinating Committee (SNCC), the Pan-African Skills Project recruited African Americans with technical skills and ‘practical work experience’ to ‘assist in the internal development of progressive African nations. . . . Pan African Skills was the brainchild of Irving Davis, who by 1970, had a long history of political activism dating back as early as 1958 . . . . After joining SNCC in 1966, Davis came under the tutelage of James Forman, who headed SNCC’s International Affair Commission. . . . Many African American activists were disillusioned with the minimal gains made under the banner of civil-rights and the co-opted politics of ‘Black-power’ and sought to place their energies in Africa, their ancestral motherland. One of the more exciting countries for African Americans was Tanzania, which by 1967, was engaged in an ambitious socialist development experiment called ‘Ujamaa’. Tanzania also became one of the leading independent African nations lending political and material support to African nations still fighting for independence, namely Rhodesia, South Africa and the Portuguese colonies of Angola, Mozambique and Guinea-Bissau. As a progressive African nation, Tanzania emerged as a political base for revolutionary activists from around the world, not the least of which included African-Americans. It was in this context that the Pan-African Skills Project was created out of the diplomatic activities of SNCC’s International Affairs Commission with Tanzania, and the individual initiative of Irving Davis, who believed strongly in Tanzania’s principles of self-reliance and commitment to Ujamaa.” (We Will Run While Others Walk: The Pan African Skills Project and Ujamaa Socialism, 1970-1980”)

Excerpts from Guilty as Charged: Malcolm X and His Vision of Racial Justice for African Americans Through Utilization of the United Nations International Human Rights Provisions and Institutions

https://elibrary.law.psu.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi…

“Thus, Malcolm X's liberating paradigm centered upon his intention to utilize the United Nations as a Pan-African forum to illustrate the international human rights violations perpetrated by the United States upon its citizens of color.

Malcolm X attempted to deconstruct the African perception of Black Americans as United States citizens, positing an identity as peoples subjected to racial oppression and colonized by white people.' Central to this construct was the theme of Pan Africanism.

In conjunction with his Pan-African efforts, Malcolm X explained the racial situation in the United States and attempted to establish alliances with the various African nations to gain their support and cooperation in his attempt to bring the United States before the United Nations for violating the "human rights of 22 million African Americans."43

Malcolm X claimed that he had pledges of support for the case against the United States and it would be prepared for submission later in the year.45

In order to facilitate his Pan-African internationalism and United Nations plan, Malcolm X established the Organization of Afro-American Unity (OAAU), patterned after the Organization of African Unity (OAU). 6 He sought to have the OAAU accredited United Nations observer status which would allow the organization to participate in the United Nations as a legitimate representative of a national liberation movement.47

On June 24, 1964, Malcolm X made public a letter sent to local and national leaders of civil and human rights organizations and to representatives of African nations in the United States. 48 The letter announced the formation of the OAAU, designed "to unite Afro Americans and their organizations around a non-religious and nonsectarian constructive purpose for human rights."'49

Several days later during the OAAU founding rally, Malcolm X stated that one of the first steps of the OAAU was to work with all other leaders and organizations interested in a program to bring the African-American struggle to the United Nations."50

Malcolm X reiterated that it was essential to internationalize the problem by "taking advantage of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, the United Nations Charter on Human Rights, and on that ground bring it into the UN before a world body wherein we can indict Uncle Sam for the continued criminal injustices that our people experience in this government."'51

On July 5, 1964, at the second rally of the OAAU, Malcolm X explained that world pressure must be brought to bear upon the United States: "[y]ou and I have to make it a world problem, make the world aware that there'll be no peace on this earth as long as our human rights are being violated in America. Then the world will have to step in and try and see that our human rights are respected and recognized." 2 Thus, with his new organization and agenda established, Malcolm X departed for Africa on July 9, 1964, to continue his efforts to gain support for his United Nations plan. 53

Malcolm X intended to pursue his United Nations plan by attending the second meeting of the Organization of African Unity in Cairo.' Malcolm X, although not permitted to address the OAU, was given the status of an accredited observer to the OAU conference." In this capacity, he submitted an eight-page document to the delegates appealing to the various heads of state for support. 56

Malcolm X's document stressed the Pan-African relationship between African-Americans and Africans. He stated: "[o]ur problem is your problem. It is not a Negro problem, nor an American problem. This is a world problem; a problem for humanity. It is not a problem of civil rights but a problem of human rights."5" Malcolm X requested the assistance of the independent African states to help bring the problem before the United Nations on the grounds "that the United States government is morally incapable of protecting the lives and the property of 22 million African-Americans. And on the grounds that our deteriorating plight is definitely becoming a threat to world peace."" He concluded: "[i]n the interests of world peace and security, we beseech the heads of the independent African states to recommend an immediate investigation into our problems by the United Nations Commission on Human Rights." 59

Malcolm X hoped the African heads of state would publicly endorse the substance of his position in the OAU's resolutions.' Instead, for his efforts, Malcolm X was moderately rewarded with a carefully worded declaration acknowledging "with satisfaction" the United States passage of the 1964 Civil Rights Bill.61 The "satisfaction" was tempered with a statement that the OAU Conference "was deeply disturbed, however, by continuing manifestations of racial bigotry and racial oppression against Negro citizens of the United States of America ... the existence of discriminatory practices is a matter of deep concern to the member states of the OAU."'62 In conclusion, the resolution urged the United States government to "intensify its efforts to ensure the total elimination of all forms of discrimination based on race, color, or ethnic origin.” 63

Although the resolution was not an endorsement of Malcolm X's United Nations plan, he accepted it and was generally satisfied with the outcome of his activities of the conference." He claimed that several African nations officially promised to support any effort to bring the problem before the United Nations Commission on Human Rights.65 In addition, Malcolm X stated that "several of them [African countries] promised officially that, come the next session of the UN, any effort on our part to bring our problem before the UN... will get support and help from them. They will assist us in showing us how to help bring it up legally. So I am very, very happy over the whole result of my trip here.”66

After his return to the United States on November 24, 1964, Malcolm X's speeches and statements elaborated on his Pan African internationalism.74 He stressed the general need for international unity in order to combat the evils that existed within the United States.75 He explained that if international unity was accomplished then African-Americans would be in position to condemn the United States as they would no longer be in the minority but rather would become the majority.7 6 In this context, Malcolm X envisioned the purpose of the OAAU as a means "to give us direct links, direct contact, direct communication and cooperation with our brothers and sisters all over the earth."'77

On November 29, 1964, Malcolm X explained that in the following weeks he would elaborate on the type of support he had received for his United Nations plan.78 He stated: "[y]ou and I must take this government before a world forum and show the world that this government has absolutely failed in its duty toward US."' 79

In addition, in a speech at a Harvard Law School Forum on December 16, 1964, Malcolm X briefly mentioned that the OAAU was trying to get the problem before the United Nations and it was willing to cooperate with any civil rights organization to achieve this goal.' ° Malcolm X mentioned the United Nations topic for the last time on February 16, 1965, just days before his death." 81

He explained the difference between civil rights and human rights: as long as you call it civil rights your only allies can be the people in the next community, many of whom are responsible for your grievance. But when you call it human rights it becomes international. And then you can take your troubles to the World Court. You can take them before the world. And anybody anywhere on this earth can become your ally.82 Malcolm X concluded that the OAAU must come up with a program "that would make our grievances international and make the world see that our problem was no longer a Negro problem or an American problem, but a human problem. And a problem which should be attacked by all elements of humanity." 3 On February 21, 1965, Malcolm X took the podium as he prepared to announce a basic unity plan to incorporate a reorganization of the OAAU and perhaps reveal where he was headed with the United Nations project.84 As Malcolm X began to speak, he was cut down by a hail of bullets from a group of assassins.”